|

Dear Commissioner Hardesty, As new Commissioner-in-Charge of PBOT, it seems like you have good intentions for transportation in Portland. You gave an inspiring speech at the virtual 82nd Ave rally last week. You’ve declared yourself a huge fan of car-free streets. And in a 2019 interview, you said that “if we’re ever going to impact the climate, we need to get people out of automobiles.” Which is why the way you’ve responded to Seth Smart’s plea for a safer Hawthorne is puzzling to me, as many of the claims you make are simply untrue. I’d like to address them here. You say that: “this year alone, six pedestrians have been killed on city streets. To date, we are thankful no people on bicycles have been killed.” It’s great that no one has died yet while biking on Hawthorne (or any other streets this year). But we still know that it’s unsafe to bike on Hawthorne (partly as evidenced by the amount of people biking on the sidewalk—a dangerous problem in its own right) and that the street’s design fails to include any safe accommodation for people on bikes. With the opportunity this project provides, don’t we make it safer to bike on Hawthorne before someone dies? We know it's unsafe to bike on Hawthorne. You say that: “it’s important to remember this is not a total redesign of Hawthorne because PBOT doesn’t have the funds for that. However, these are important public safety investments that will make our streets safer.” The Pave and Paint Project’s budget is over $600,000 (it might be more; this is just the last estimate I heard). Last year, PBOT paid a $395,000 settlement—more than half the cost of the Pave and Paint Project--to the Smart family because Hawthorne's design was found to be negligent. With a deadly center turn lane and no bike infrastructure on Hawthorne, at least several people are likely to be killed or maimed on the street in the coming years, and additional settlements will need to be paid. Alternative 3b—the safer design that Fallon’s father, street safety advocates, nearly 3,000 neighbors and over 100 businesses are asking for—will likely save PBOT money. Additionally, PBOT has given no indication that Alternative 3b would cost more money than Alternative 2—and there’s no reason to believe that it would, since both designs are simply a different arrangement of paint on the ground. Why wouldn’t we choose the arrangement of paint that is safer for people walking and biking? You say that: "by providing a center turn lane, we can lessen the chance that pedestrians will be hit by turning cars, one of the leading causes of serious injuries and fatalities to people walking.” But PBOT is not installing a center turn lane east of Chavez—where Fallon Smart was killed—because a center turn lane already exists there. This center turn lane has existed for decades, and has done nothing but cause physical harm to people crossing the street by allowing people to drive faster. You say that: “islands, better lighting and crosswalks make it easier and safer for people walking to cross the street by giving them a refuge from traffic and by making them more visible to drivers.” It’s true that islands will make Hawthorne safer to cross. Better lighting is great, too. But Fallon Smart was killed in broad daylight, so better lighting would have done nothing to save her life. And since making pedestrians visible to drivers at intersections is crucial for safety, Alternative 3b is a vastly better design, since it eliminates parking spaces at intersections, which dramatically improves sightlines. Meanwhile, Alternative 2 essentially doesn’t remove any parking at intersections, so pedestrians will still need to stick their necks out to peer around 7-foot-tall trucks parked right up to the corner of intersections: You say that: “had bike lanes been installed, the pedestrian islands would have had to be significantly smaller and thus would have provided less protection.” First of all, Fallon was not killed in the center turn lane because there was a narrow pedestrian island—she was killed because there was no pedestrian island at all. But more importantly, to say that she would have been “provided less protection” if bike lanes had been installed is patently false. If bike lanes had been installed, there would have been no center turn lane, so the person who murdered her would not have been physically able to speed around the stopped cars in the center turn lane. That’s why Alternative 3b is a much safer design. According to PBOT, Alternative 2 provides “8- to 10-foot” refuge islands, while Alternative 3b provides 6-foot refuge islands. There’s no doubt that an 8-foot island would provide more comfort and protection than a 6-foot one—but how much more? Is that two feet of concrete so important for pedestrian safety that it’s worth sacrificing safety for people biking and scootering entirely? Is that two feet of concrete so important for pedestrian safety that it’s worth continuing to encourage people to bike and scooter on the sidewalk for years to come—at the expense of pedestrian safety? You say that: “the project will reduce the current lanes from two in each direction to one in each direction plus the center turn lane." Again, this is incorrect; there is no planned lane reduction for Hawthorne east of Chavez, which is the segment Fallon’s father is asking you to make safer. A lane reduction here from three lanes (currently) to two lanes (Alternative 3b) would slow drivers down, reduce crossing distances, and make it physically impossible for drivers to use the center turn lane to swerve around other drivers who are stopped for pedestrians in unmarked crosswalks, which is how Fallon was killed. Even with the “high priority” median islands PBOT says it plans to build (none of which are east of Chavez), there would still be many intersections without them. Narrowing the street to two travel lanes will automatically make every intersection safer. You say that: “this has multiple safety benefits for pedestrians. First pedestrians only have to cross one lane of traffic at time. If bike lanes were installed, pedestrians would have to cross two lanes of traffic, a motor vehicle lane and a bike lane. The second benefit will come from the lower speeds that will result from fewer travel lanes." It’s disingenuous and factually incorrect to equate crossing a bike lane to crossing a car lane. Bikes usually weigh less than fifty pounds and top out at 20mph, while cars and trucks weigh thousands of pounds and routinely gain speeds triple that. People on bikes are heavily incentivized to not crash into people since it would put them at serious risk of personal injury—unlike drivers, who are enshrouded in thousands of pounds of steel and can speed directly into crowds of people and walk away without a scratch. And thousands of people are killed by cars every year, while almost none are killed by bikes. Finally, Alternative 2 does not reduce the amount of travel lanes east of Cesar Chavez—and widens the travel lanes west of Chavez. Wider travel lanes are shown to increase speeding. How exactly will this design prevent speeding? Lastly, you say that: “the adopted design preserves space for future improvements for pedestrians, including wider sidewalks and curb extensions. Hawthorne is a Major City Walkway and thus the potential for future improvements is a significant factor to consider.” As you mentioned, the Pave and Paint Project does not involve any permanent construction that would prevent widening sidewalks or building more curb extensions in the future. Since it’s only paint, Alternative 3b preserves space for wider sidewalks and curb extensions just as much as Alternative 2—and keeps pedestrians and active transportation users safer while the neighborhood awaits a more extensive capital reconstruction that is likely no less than a decade away. ~~~ In order for Portland to make progress on our transportation goals, micromobility safety cannot be an afterthought. Providing people safe, attractive alternatives to driving is the only way to lure people out of their cars, which is the only way to solve the vicious cycle of increasing congestion, carbon emissions, and vehicular violence we find ourselves in. Continuing to relegate bikes and scooters to side streets will not cut it; studies show that a complete network of high-quality protected micromobility lanes on commercial and arterial streets is the single best way to create the mode shift necessary to achieve our safety and climate goals. According to our 2030 Bicycle Plan, bicycling:

The plan goes into much more detail about why each of these is true, but the point is: This isn’t just about catering to “the biking community”—it’s about creating a safer, healthier, more climate-friendly, more economically friendly, more equitable, more fun, and more liveable city. The stated purpose of the Pave and Paint Project is to “take advantage of a near-term opportunity.” Why wouldn’t we seize this opportunity to move the needle on achieving these benefits? For the sake of Portland’s future, please reconsider. Sincerely, Zach Katz

0 Comments

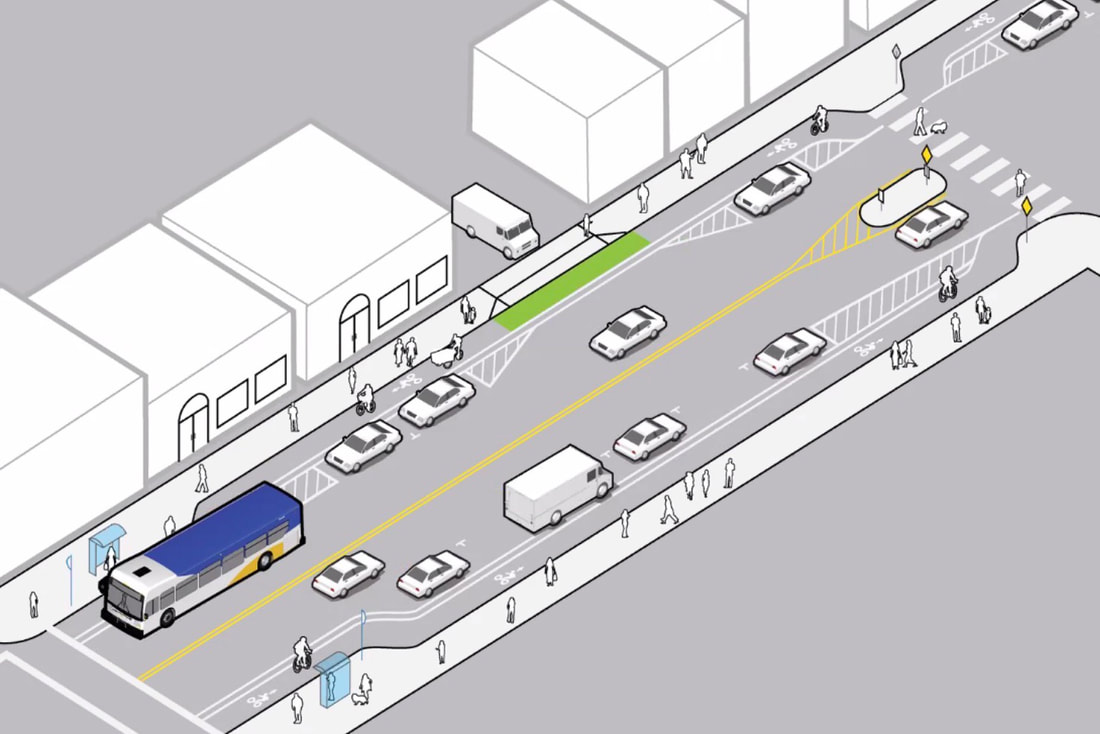

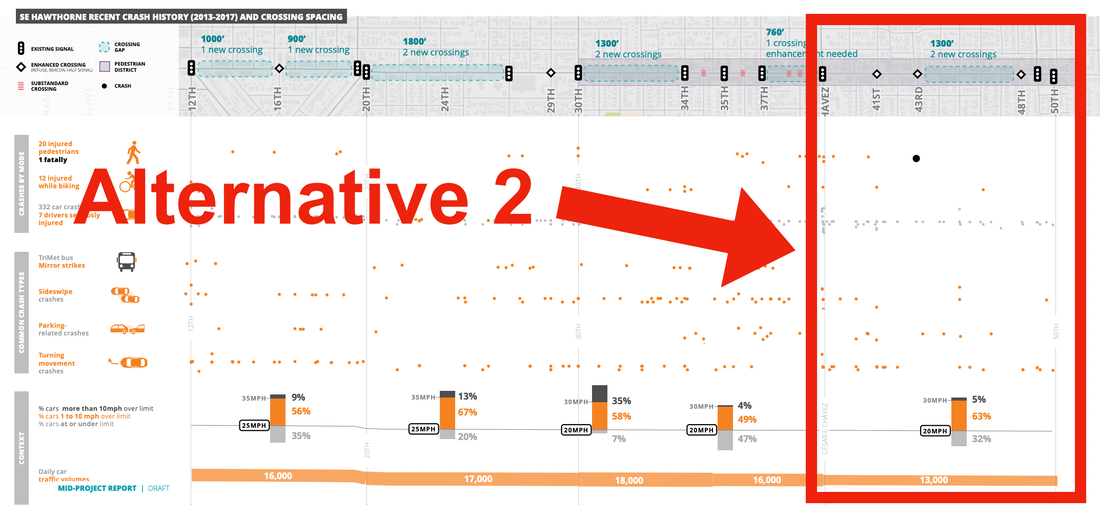

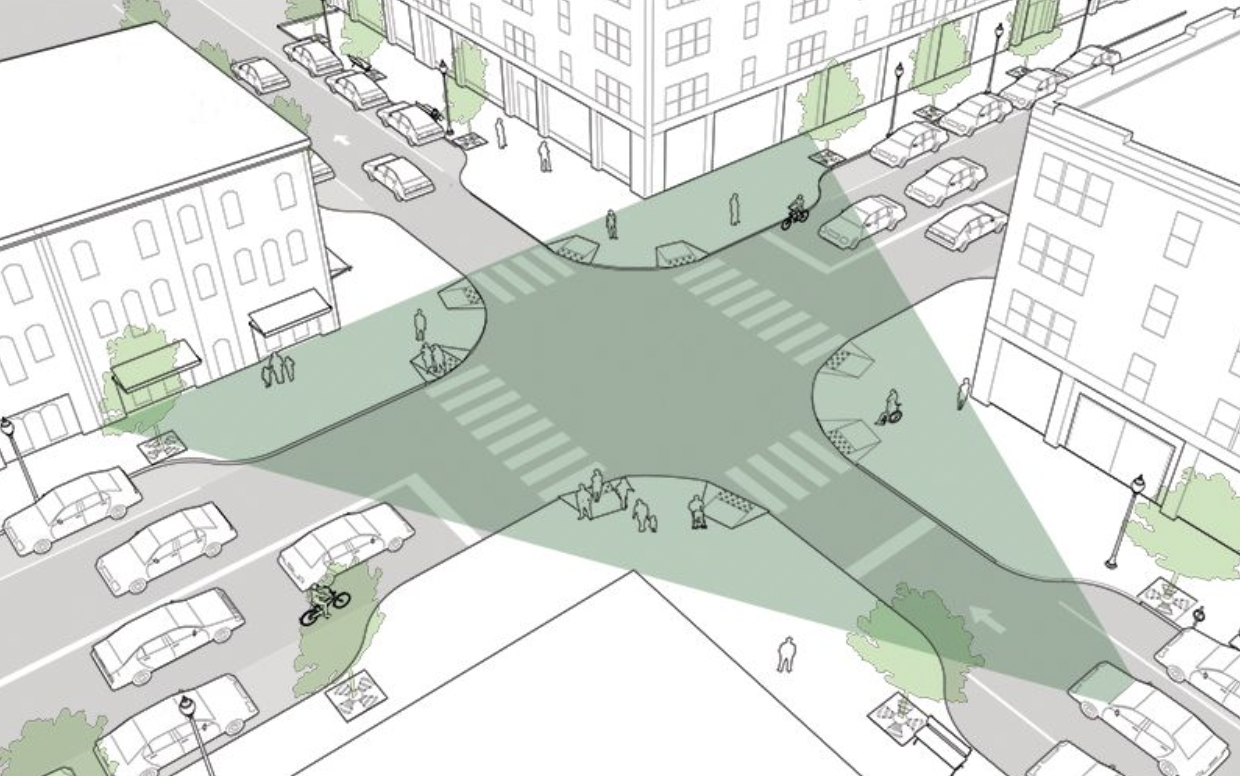

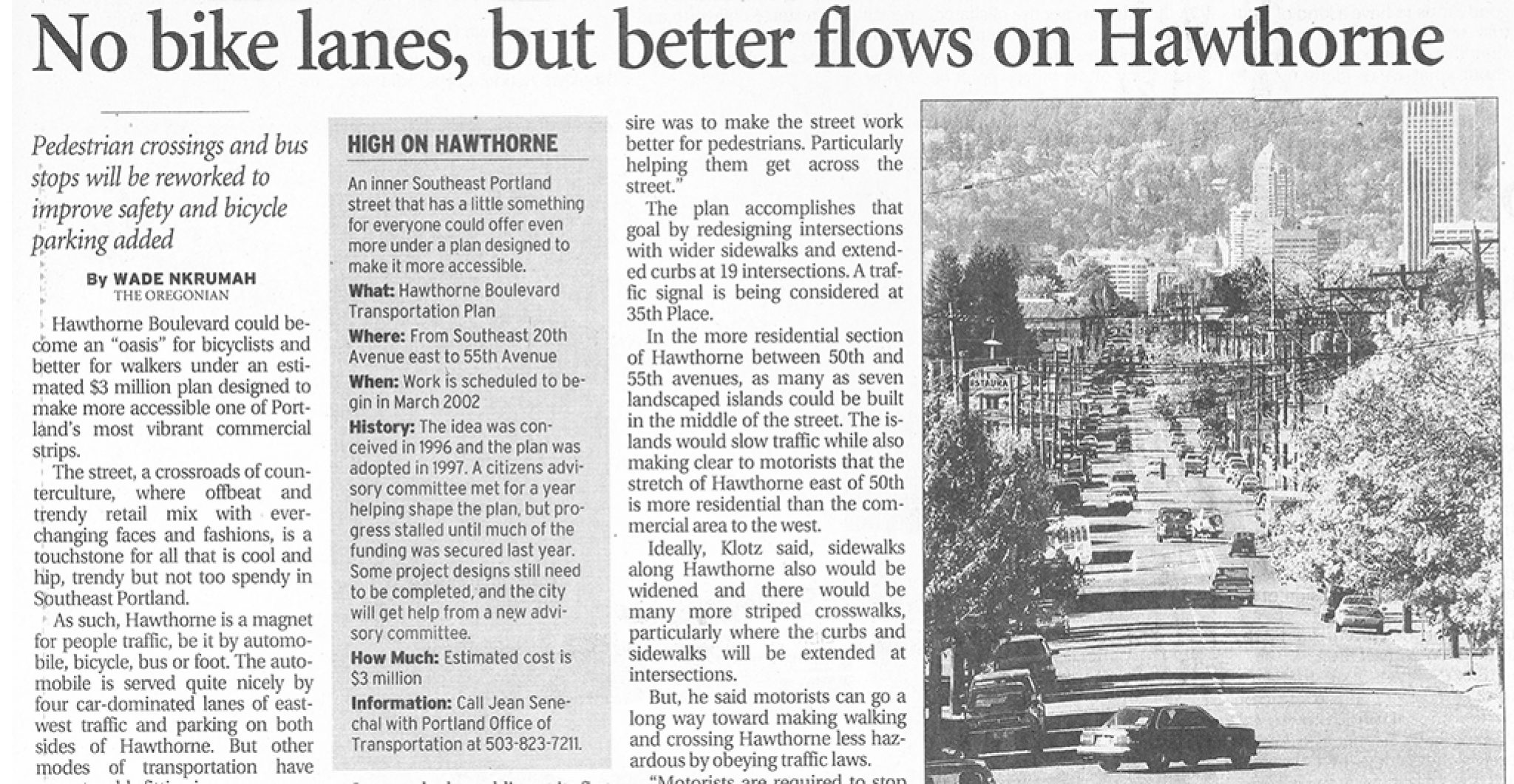

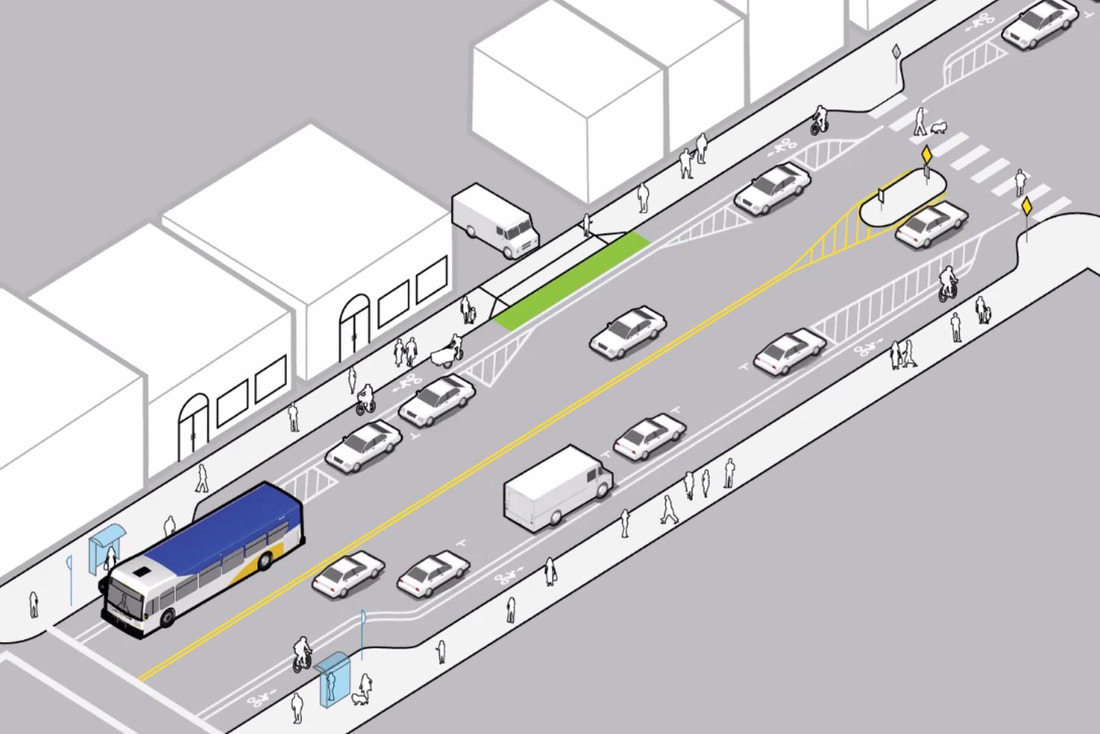

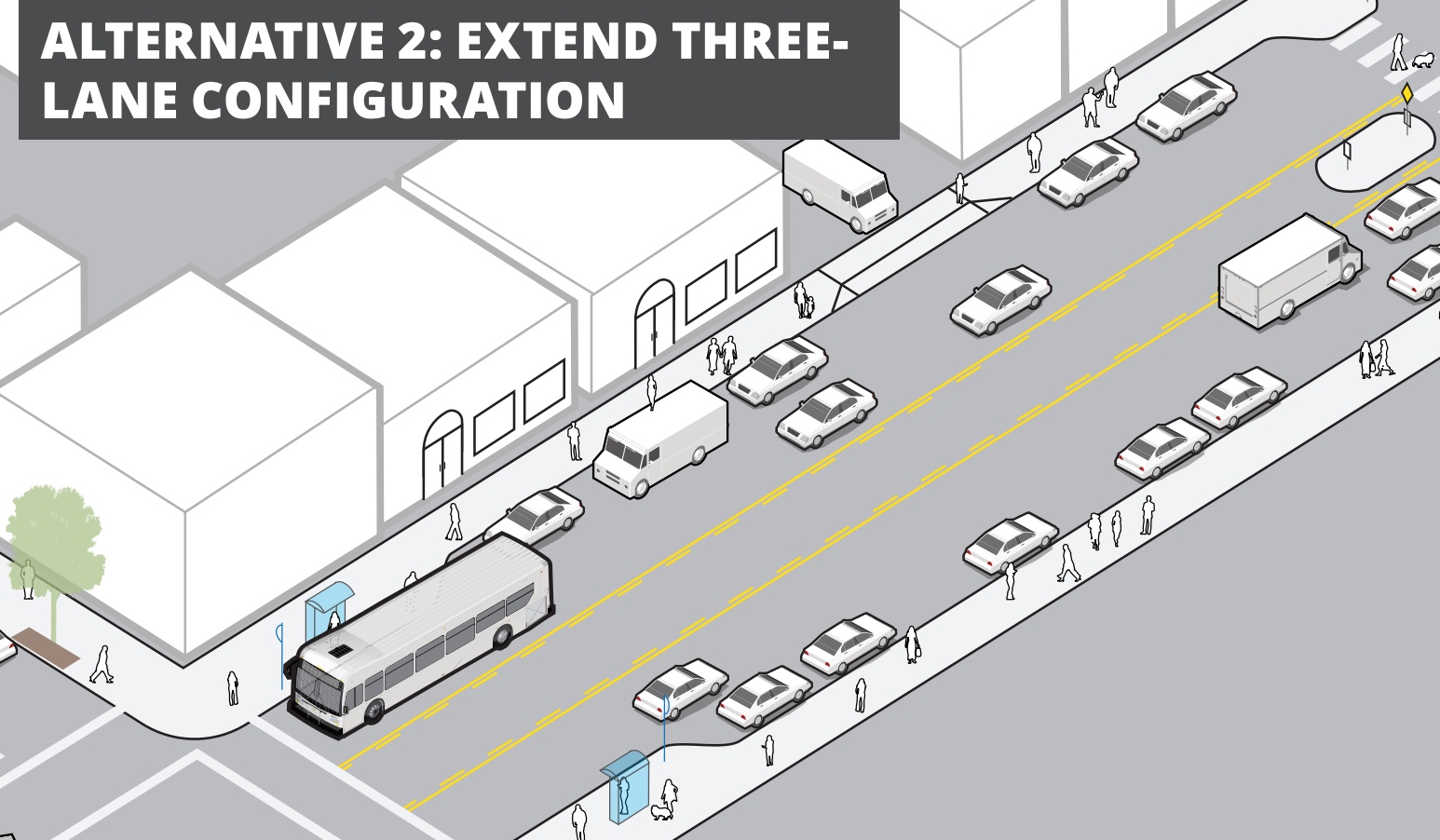

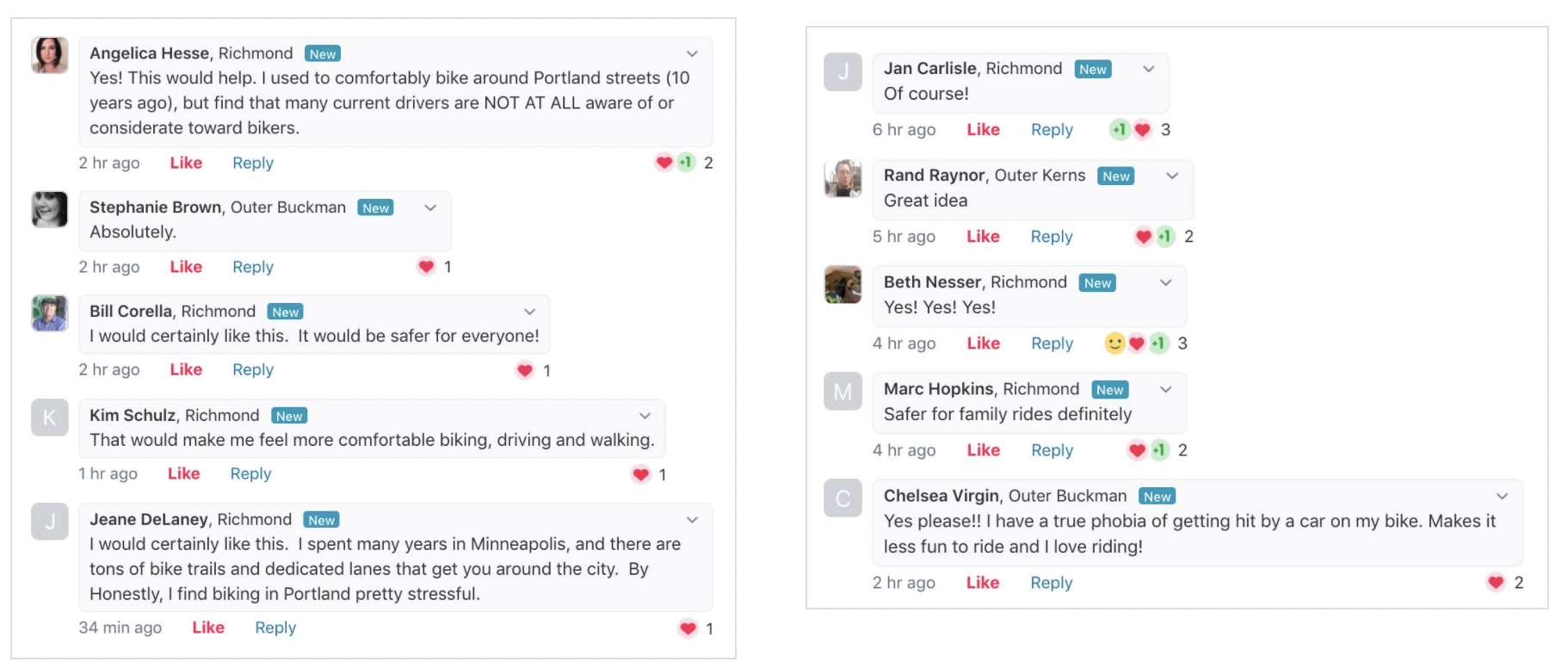

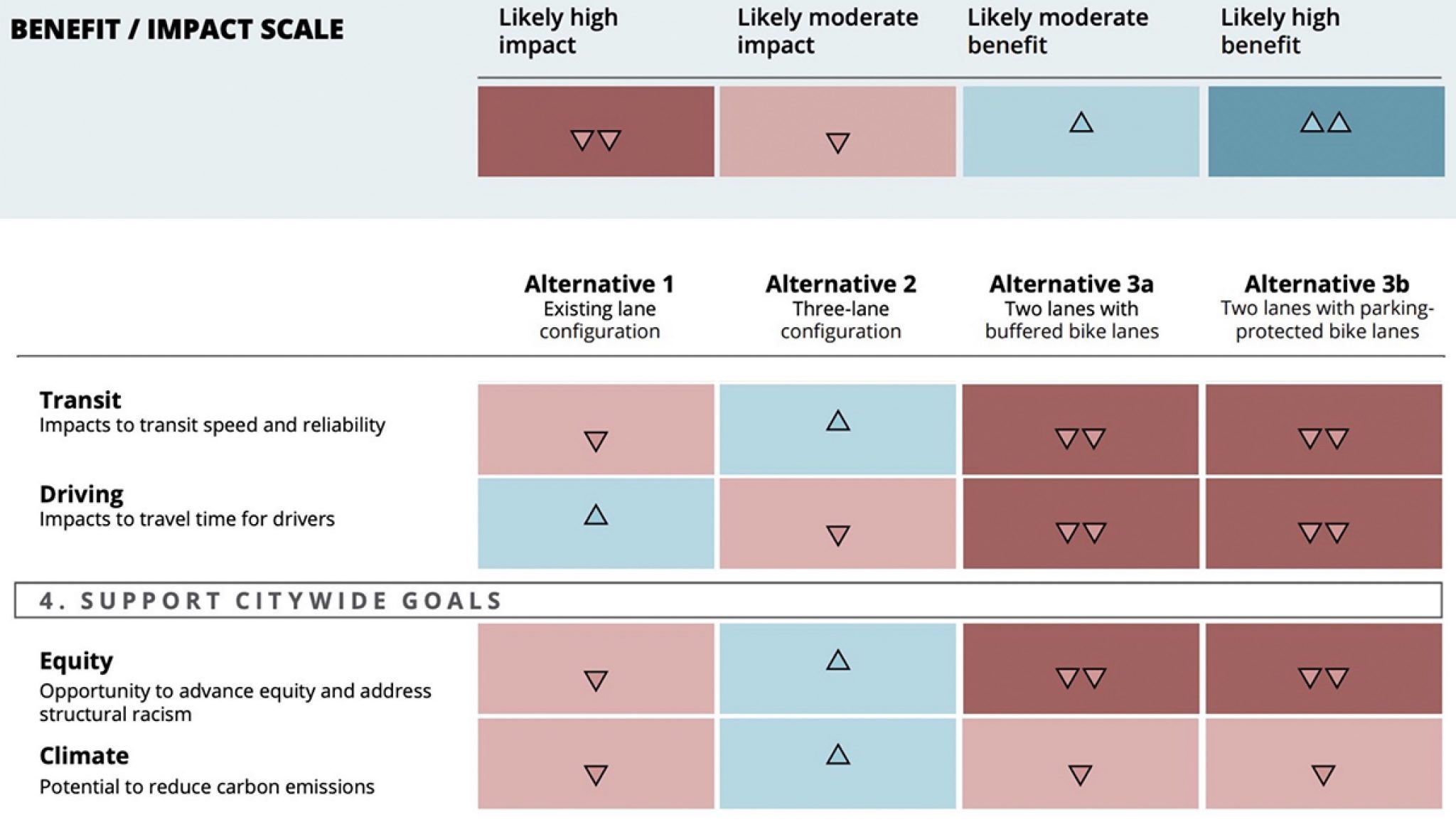

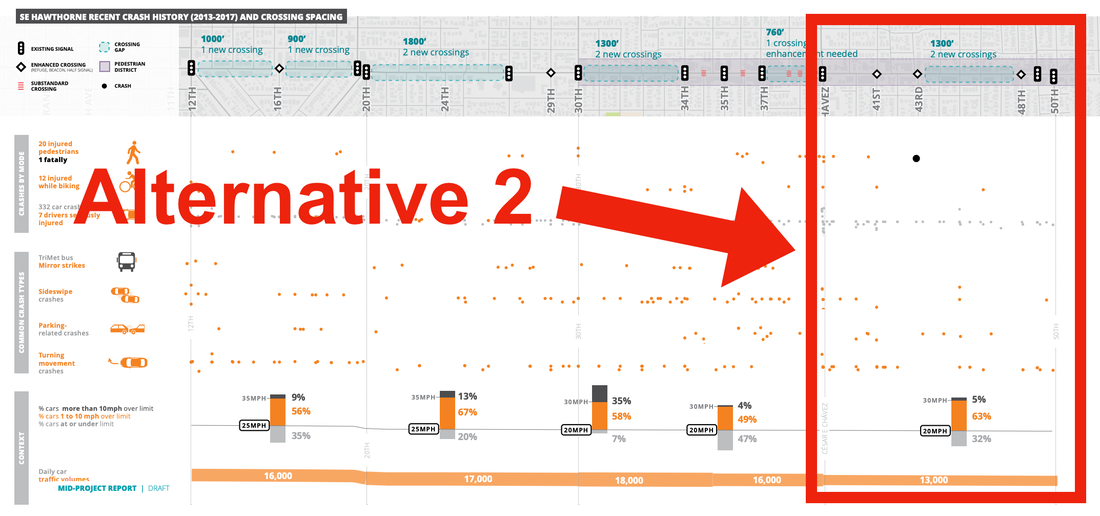

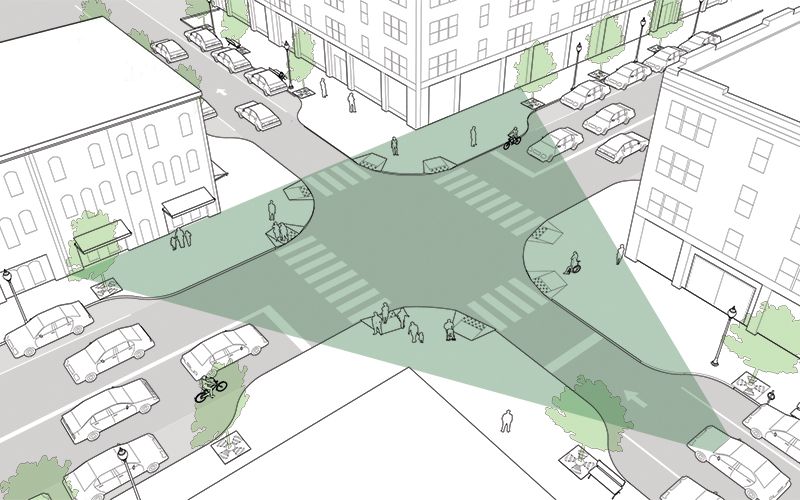

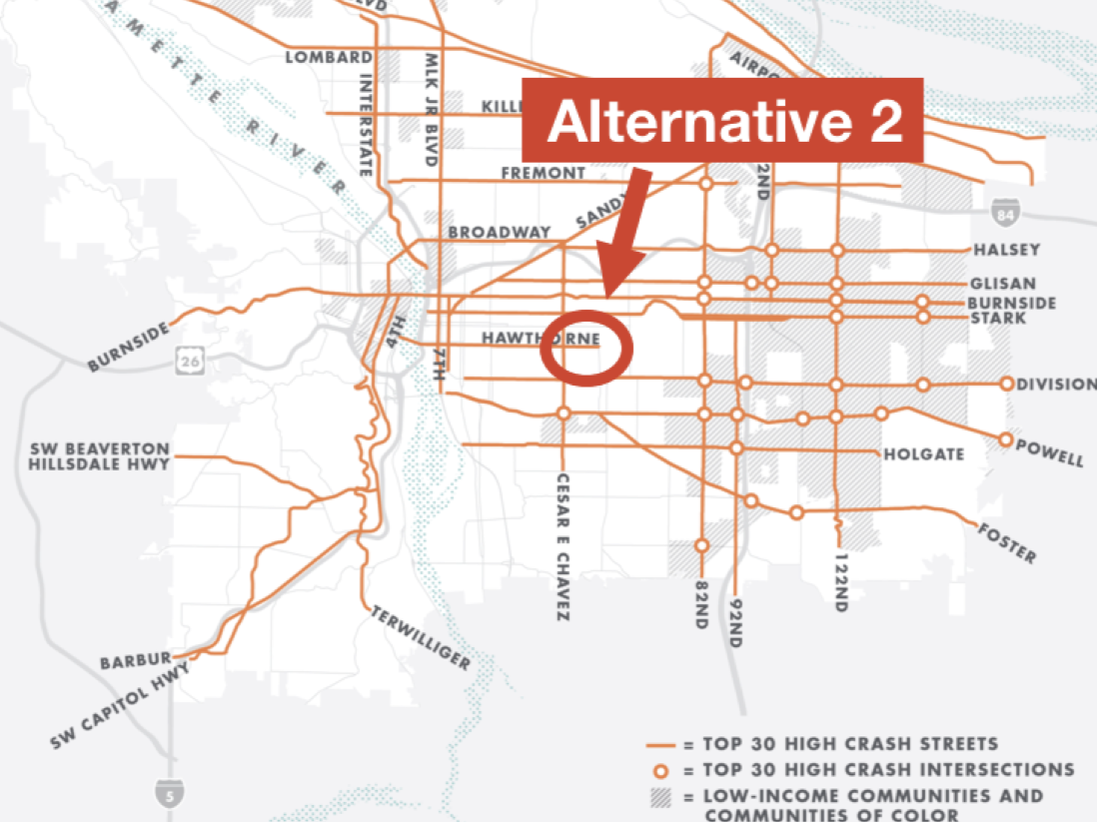

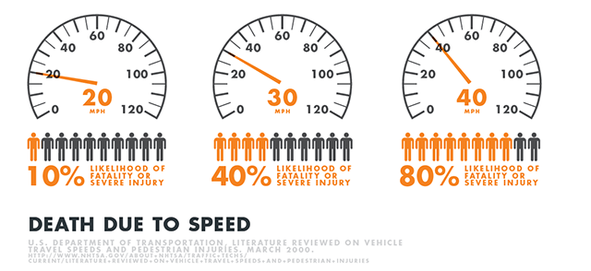

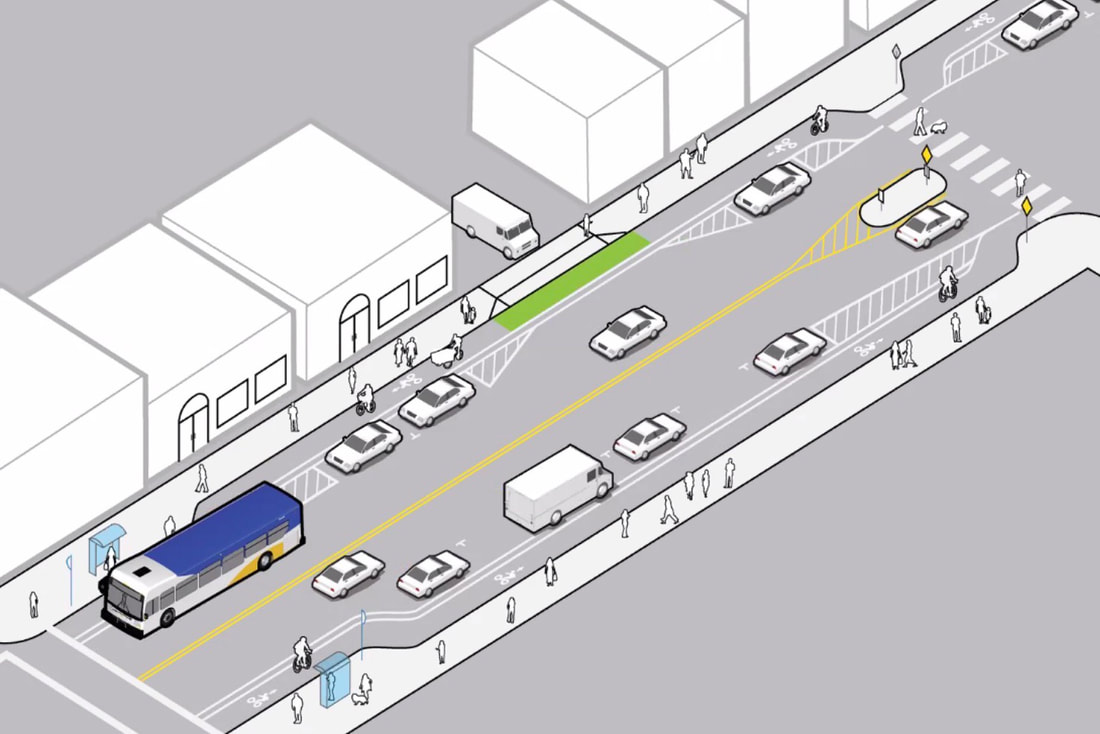

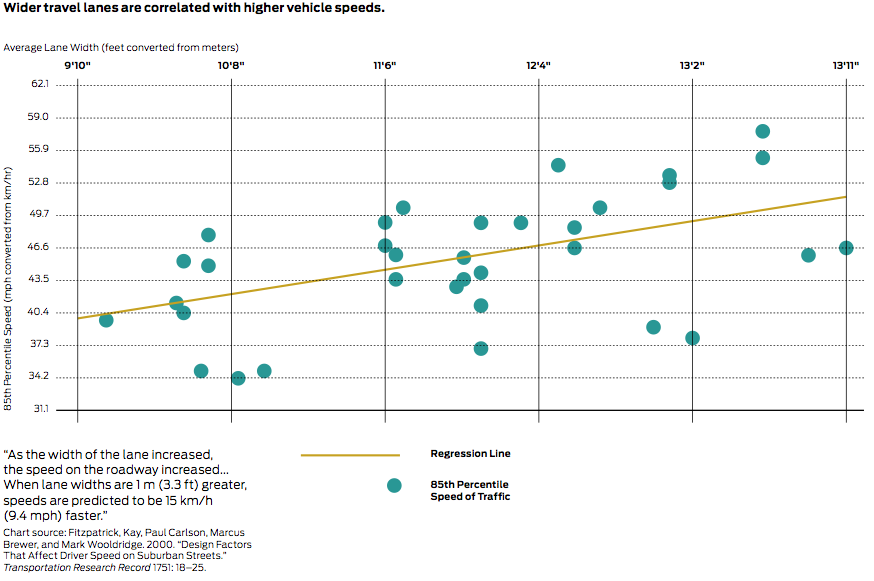

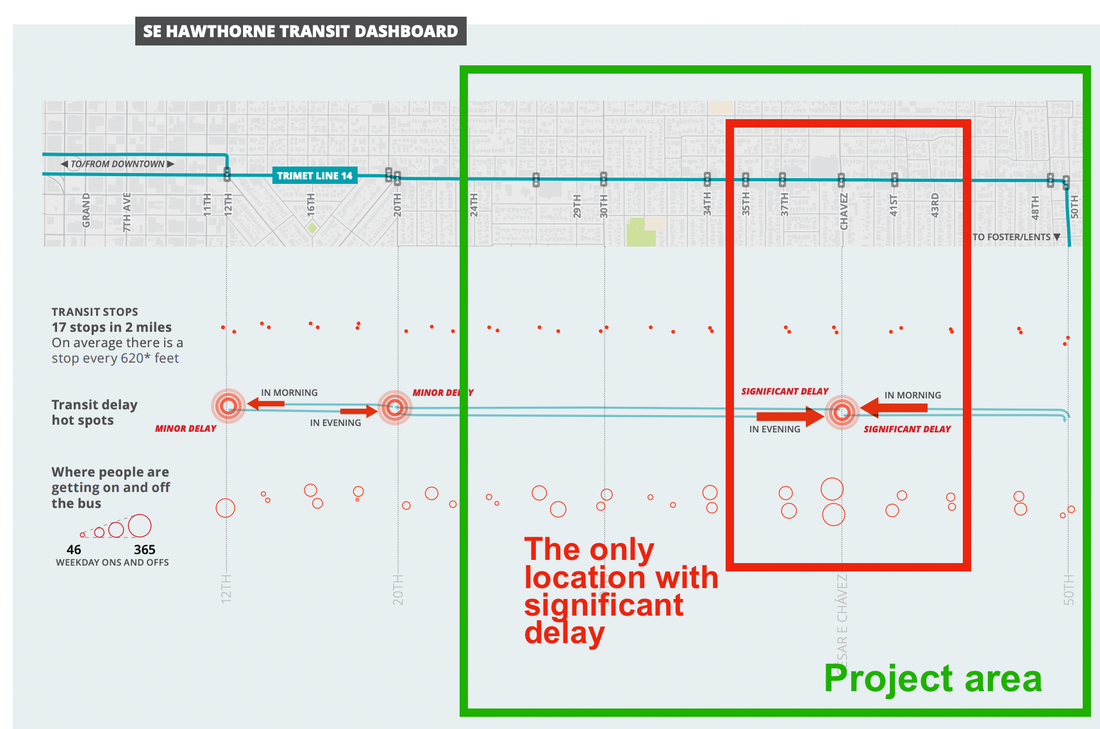

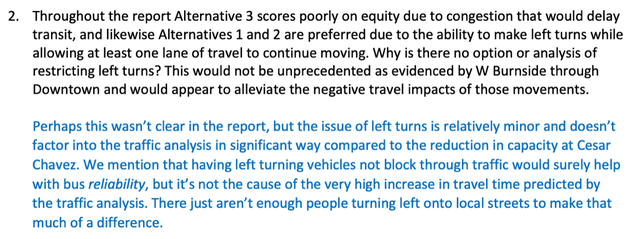

Debunking The Hawthorne Decision Report: How PBOT Lied About Bike Lanes—And Got Away With It3/24/2021 Announcement: As of April 4th, 2021, we've started a GoFundMe campaign to sue PBOT and hold them accountable for their deception detailed in this article. Please help! Last February, the Portland Bureau of Transportation (PBOT) announced the Pave and Paint Project, with plans to repave and re-stripe Hawthorne Boulevard from SE 24th to SE 50th Ave. “We are looking to improve safety and better serve businesses on Hawthorne,” PBOT’s Hannah Schafer said. “We know how important Hawthorne is in our road network and we think this is an opportunity to do something big and bold.” Hawthorne is an extremely dangerous street for people walking, biking, and driving (it's one of the city's High Crash Streets and sees hundreds of crashes every year), so safe streets advocates were excited. “Big and bold,” many thought. “This is Portland, for heaven’s sake. It’s 2020, more people are biking than ever, and it’s even in the city’s official plans. Surely that means they’re going to be adding bike lanes!” But at the first open house in March—in a room full of slick posters and interactive boards that encouraged people to “put a sticker here if you want more trees!” and “put a sticker there if you want more crosswalks!”—there was no mention of bike lanes. This was the first opportunity to redesign Hawthorne since 1997, and they weren’t even asking anyone if they should include protected bike lanes. Local street safety advocates sprung into action. A website was made. Business outreach was conducted (most were enthusiastic). Posters were stapled to telephone poles, and local politicians (Sarah Iannarone, Chris Smith, Teressa Raiford, and Sam Adams, to name a few) pledged their support. In May, as a result of months of activists' volunteer work, PBOT finally decided to consider bike lanes. They released two potential designs: Alternative 3b, which included protected bike lanes, and Alternative 2, which did not. (There were two other options—Alternative 1 and Alternative 3a—but Alternative 1 proposed keeping the street entirely unchanged, and Alternative 3a proposed unprotected "door-zone" bike lanes, which are proven to be deadly, so we’ll disregard those options). Unfortunately, Alternative 2—the one without protected bike lanes—does not meet the real needs of a street like Hawthorne Boulevard. It would not include any way for people to safely bike to and between the homes, parks, schools, and businesses along and near Hawthorne. Instead, it would replicate the current design problem the street faces, where people either bike on the sidewalks (increasing risks at intersections and encroaching on those walking and using wheelchairs) or in the street with buses and trucks (risking themselves). Many people feel so unsafe they avoid the street altogether, weakening our local businesses, or they drive instead, causing congestion and worsening air and noise pollution. Alternative 3b best aligns with our city’s visions, goals, and policies for this important corridor, lined with hundreds of homes and businesses, ferrying thousands of people each day by foot, wheelchair, scooter, bike, skateboard, bus, and car. Alternative 3b creates one of the best main streets in our region, and a pleasant, safe, and vibrant place for our community. It welcomes and is safe for everyone, no matter how we travel. For the sake of the corridor’s long-term vitality, Alternative 3b is the choice for our community and local businesses. With overwhelming neighborhood and business support for Alternative 3b, it seemed certain it would be built. But there were roadblocks ahead. In September, PBOT released its Alternatives Evaluation, along with a public survey where PBOT made strong, graphical claims that bike lanes are bad for both "equity" and "climate." One might assume that these claims were supported by nuanced, in-depth analysis. But they weren’t. Not even a little bit. Unless you attended September’s Bike Loud PDX meeting or read PBOT’s lengthy Q&A with the Bicycle Advisory Committee, you wouldn’t have known that the sole justification for these claims was a projected transit delay at Cesar Chavez Boulevard —a delay PBOT later admitted would have been resolved by simply including a bus/bike “mixing zone” (a common design tool for PBOT) at that one intersection. Neither the Evaluation Report nor the public survey were ever updated to reflect this. Shortly after releasing their misleading evaluation and survey, the Hawthorne Boulevard Business Association—unaware of the mixing zone solution—cited “equity and climate concerns” in their letter to PBOT explaining why they can’t support bike lanes on Hawthorne. Local residents, businesses, neighborhood associations, and transit riders in East Portland were given Zoom presentations by PBOT staff and told: Bike lanes are bad for equity. They’re bad for climate, too. Now please fill out this survey and tell us what you think about bike lanes. Despite this setback, public and business support continued to grow for bike lanes. A new petition garnered over 2,500 signatures in less than two weeks. Children made heartfelt pleas for protected bike lanes in order to be kept safe while using the street. Business owners talked about how excited they are for bike lanes to bring them new customers. But it wasn’t enough. In February, PBOT announced that Commissioner Hardesty had chosen Alternative 2, attributing her decision to many of the claims that PBOT makes in their Decision Report. Many people and organizations recognize that Alternative 2 was the wrong decision. The Bicycle Advisory Committee and the Planning and Sustainability Commission have each written letters about how PBOT's plan fails to adhere to the Transportation System Plan (TSP) and Bicycle Plan for 2030, and how "there exists a continued chasm between our publicly-stated goals and the outcomes that are achieved." But most people don’t realize the extent to which PBOT fabricated the truth to justify it. PBOT used racial equity and climate justice claims—that not only weren’t grounded in any facts, but run completely orthogonal to data-supported equity- and climate-friendly urban planning best practices—to justify a street design that data shows will decrease safety (and/or maintain currently unsafe conditions), and maintain current inequitable and anti-climate outcomes. In their Decision Report, PBOT makes many claims for why Alternative 2 is supposedly the best option. They use seven criteria for their analysis: Overall Safety, Pedestrians, Transit, Emergency Vehicle Response, Low-Stress Bicycle Access, Flexible Curb-Zone Space, and Citywide Goals on Equity and Climate. With even just a little scrutiny, it’s obvious that most of their claims are disingenuous, misleading, or plain untrue. Let’s take a look. 1. Overall SafetyPBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 is best for overall safety.” Why it’s false: Alternative 2 does nothing to improve safety east of Cesar Chavez, and only makes marginal safety improvements west of Chavez. Alternative 3b is best for overall safety by calming traffic and making the street safer for all modes of transportation. PBOT says that “safety improvements are a top priority for this project,” and that they are taking a “data-driven approach, looking at crash data to find the most effective designs to reduce serious injury and fatal crashes.” They claim that “Alternative 2 is best for overall safety.” But Alternative 2 is the exact same design that currently exists east of Cesar Chavez Boulevard, which is a High Crash Street. This stretch of Hawthorne has seen dozens of crashes in 2013-2017 alone, and its deadly road configuration led to Fallon Smart’s murder in 2016. PBOT continues (all of the following block quotes in this essay are directly copied from the Decision Report): “In looking at crash patterns on Hawthorne, our team determined that we need designs to address the serious crash types occurring most often on Hawthorne: pedestrians and bicyclists crossing Hawthorne, and crashes involving turning vehicles hitting pedestrians, bicyclists, or other vehicles.” —PBOT What about people biking on Hawthorne (and not just crossing it?) While the (reported) number of cyclists who have been hit by drivers on Hawthorne may be lower than the amount of crashes involving pedestrians, these types of crashes still happen, and will continue to happen unless we build protected bike lanes to prevent them from happening. Ignoring numbers is easy; it’s much easier to recognize a problem when you see it for yourself. Watch this video of a crash that occurred on SE 32nd and Hawthorne just a few months ago (WARNING: EXTREMELY GRAPHIC): This is what happens on streets without protected bike lanes. People on bikes and scooters are forced to ride with speeding, inattentive drivers, and the results are often gruesome—or deadly. Protected bike lanes on Hawthorne are important for many reasons, but preventing people from being injured and killed by drivers is a good enough reason alone. PBOT continues by saying that one of the “most serious crash types occurring most often on Hawthorne'' is “crashes involving turning vehicles hitting pedestrians, bicyclists, and other vehicles.” As PBOT’s Vision Zero policy states, one of the best solutions to this problem is better visibility at pedestrian crossings. But further in the Decision Report (see section 6 on Flexible Curb Space), PBOT implies that removing parking at intersections to improve sightlines for turning vehicles is unthinkable because it would mean less space for parking, street seating, and other curb zone uses. If safety improvements are a "top priority" for this project, why is this not a welcome tradeoff? “Reducing Hawthorne from four lanes to three lanes with Alternative 2 is expected to reduce all crash types on the boulevard by 29%, including the most prevalent crash types that involve pedestrians and turning vehicles. Again, PBOT ignores the fact that Alternative 2 only reduces the amount of lanes on Hawthorne west of Cesar Chavez. East of Cesar Chavez, Hawthorne already is three lanes. Keeping it exactly the same will do nothing to make it safer. “With the refinements, Alternative 2 augments and strengthens the neighborhood greenway network for bicyclists. Our greenways are among the safest bike routes in the city.” Even if PBOT had proposed a concrete plan to strengthen the greenway network (which they haven’t—they’ve only given vague promises of “potential future improvements”), this shouldn’t come at the expense of improving safety for people who choose to (or, for essential workers, need to) ride bikes on Hawthorne. “Alternative 3 would reduce Hawthorne from four lanes to two lanes with bike lanes. PBOT does not have experience with this type of lane reduction but national studies indicate that left turn crashes are reduced when turn lanes are added on urban 2-lane roadways. Once again, Alternative 2’s turn lane will do nothing to reduce left turn crashes on Hawthorne east of Cesar Chavez, because this section already has a turn lane, and it’s caused enough turning-related pedestrian, bike, and car crashes to qualify this section of Hawthorne as a High Crash Street. Alternative 2 does nothing to fix this dangerous design—and even plans to replicate it on the rest of Hawthorne. PBOT is incorrect that they lack experience with this type of lane reduction. In 2012, the Division Streetscape Project reduced Inner SE Division from four lanes (technically, three lanes, since the outside lanes were AM/PM alternating pro-time parking) to two lanes. The Project Report states that this lane reduction “increased safety, access, and visibility for pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users,” and “improved traffic operations throughout the corridor.” “Given that Alternative 3 does not include turn lanes, we would not expect a decrease in left turn crashes. In Alternative 3, we expect pedestrian crashes to be reduced by 31 percent where median refuge islands are installed, and these islands would also reduce crashes for bicyclists crossing Hawthorne.” Two-lane commercial main streets like NW 23rd or NE Alberta are safer for all modes, boast less crashes, are not High Crash Streets—and do not have turn lanes. Hawthorne, on the other hand, is scarred with numerous serious crashes and is a High Crash Street. Clearly, turn lanes are not a solution to decrease left turn crashes or increase pedestrian safety. “In Alternative 3, the addition of bike lanes to Hawthorne would increase the number of cyclists using Hawthorne. Given that a significantly higher volume of people on bikes would be using Hawthorne, it is difficult to predict how this will affect overall bicycle crashes. Physically separated bicycle facilities, which would be present for a portion of Alternative 3b, have lower crash rates than traditional and buffered bike lanes. Yes, the addition of bike lanes would increase the number of people on bikes (and e-scooters, and skateboards, and rollerblades...). And yes, although it’s difficult to predict how many crashes would occur as a result of this increase, physically separated facilities have lower crash rates than traditional and buffered bike lanes. Bingo! Additionally, protected intersection designs can reduce crashes at intersections. Unfortunately, the current curb extensions, configuration of Hawthorne, and scope and budget constraints of this project do not allow for protected intersection designs or physical separation at intersections. Overall, Alternative 3 is predicted to reduce crashes over today’s design, but not as much as Alternative 2.” But then, PBOT implies that the lack of possibility for physically protected intersections is a reason to not build protected bike facilities at all--which might be a valid reason if protected intersections were standard for all new bike lane projects. But they aren’t. None of PBOT’s new protected bike lane projects—NE Halsey, NE Weidler, NW Front, and NW Broadway, to name a few—include protected intersections. For virtually all new protected bike lane projects, PBOT uses other proven methods to improve safety at intersections, like adding “cross-bikes” and removing parking at intersections to improve sightlines for turning vehicles (a design treatment this very report acknowledges will successfully reduce turn-related bicycle crashes for Alternative 3b). While true protected intersections may be outside the design and funding scope of this particular project, it's inaccurate to say that the "configuration of Hawthorne...does not allow for protected intersection designs." Joe Mangan, a Street Design Specialist in Seattle, created an innovative concept for a protected intersection on Hawthorne and SE 34th, which would work for most intersections on Hawthorne—even those with curb extensions: “Both Alternatives 2 and 3 are expected to reduce speeding.” East of Cesar Chavez, Alternative 2 will not reduce speeding, because it proposes no changes whatsoever to the street’s existing design. West of Cesar Chavez, Alternative 2 is expected to increase speeding. NACTO guidance states that lane widths are correlated with increased speeds. One study indicates a 2.9mph increase per foot of lane width, which would mean an 8.7 mph speed increase on this stretch of Hawthorne. This graphic shows how higher speeds increase the risk of fatality in collisions: Alternative 2’s 12-foot travel lanes and center turn lane will cause drivers to speed more, making the street more dangerous for all users. By narrowing the street to two 10-foot travel lanes, Alternative 3b will calm traffic and provide the most amount of safety for people walking, biking, and driving. 2. PedestriansPBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 is the best option for pedestrians.” Why it’s false: Alternative 3b is the best option for pedestrians by calming the street, improving sightlines at intersections, creating median refuge islands for safer crossing, and getting e-scooters and bikes off of the sidewalk by giving them a safer place to ride. The Pave and Paint project presents an opportunity to make dramatic, needle-moving improvements to pedestrian safety. But with Alternative 2, PBOT has settled for marginal improvements West of Cesar Chavez Boulevard—and no improvements at all to Hawthorne east of Cesar Chavez. In their letter to PBOT Director Warner, the Bicycle Advisory Committee points out that Alternative 2 is “the exact three-lane cross section without a median island. And while Alternative 2 offers 10-foot median refuge islands at some intersections, the only reason these wide refuge islands are necessary in the first place is because of its 12-foot travel lanes and center turn lane, which make the street significantly more dangerous by inviting drivers to speed (turn lanes are also often used as a “passing lane” by aggressive drivers). Alternative 3b also offers median refuge islands, along with more pedestrian safety benefits like narrower lanes, shorter crossing distance, and dramatically improved sightlines at intersections. And while Alternative 2’s 10-foot median refuge islands are wider than Alternative 3b’s 6-foot islands, Alternative 2’s wider travel lanes and center turn lane—which are proven to increase driving speed and decrease safety for all modes—negate any advantage its slightly wider refuge islands would otherwise offer. NACTO guidelines state that 6-feet is the minimum width for refuge islands, and that wider crossing islands are preferable. However, NACTO guidelines also state that protected bike lanes are essential for streets with an Average Daily Traffic Volume (ADT) of more than 6,000 cars per day. Hawthorne has an ADT of 18,000 cars per day. “Our team re-evaluated Alternatives 2 and 3 to consider the potential to add pedestrian space. Within the constraints of this project, sidewalks cannot be widened. However, Alternative 2 offers the most potential for sidewalk widening in the future by preserving the most curb zone space that could be converted to more sidewalk space over time. Hawthorne absolutely needs wider sidewalks, but they should not come at the expense of bike lanes. Since this is only a re-striping project and not a permanent reconstruction, painting protected bike lanes will not prevent sidewalks from being expanded in the future. “Also, Alternative 2 allows for wider median refuge islands than Alternative 3, providing more comfort for pedestrians crossing the street.” The best way to meaningfully speed up transit on Hawthorne would be to make the street a car-free busway. While a busway is outside the scope of the Pave and Paint Project, the 10-foot concrete median islands proposed in Alternative 2 would interfere with both this future busway (since buses wouldn’t need the extra turn lane) and the city's ability to add protected bike lanes in the future. “Alternative 2 offers the best configuration for pedestrians and bicyclists crossing at unmarked, legal locations. In this alternative, pedestrians and people on bikes would only have to navigate two lanes of traffic. The center turn lane would also offer a refuge in unexpected circumstances.” It’s inaccurate to say Alternative 2 offers the “best configuration” because “pedestrians and people on bikes would only have to navigate two lanes of traffic,” because Alternative 2 has three lanes of traffic—two travel lanes and a center turn lane. Alternative 3b, on the other hand, truly only has two lanes of traffic. More importantly, Fallon Smart was killed while crossing Alternative 2 in an “unmarked, legal location.” The center turn lane did not “offer a refuge” to her in “unexpected circumstances”—it offered her a false sense of security, with deadly consequences. Wider roadways are proven to encourage higher speeds and lead to more injurious and fatal crashes. A center turn lane only adds to this danger. Meanwhile, two-lane commercial streets without turn lanes, like NW 23rd and NE Alberta, are much easier to cross and are safer for all modes. “In Alternative 3, people crossing would still have to navigate four streams of traffic at the same time (two bike lanes and two vehicle lanes), with nowhere to pause if traffic fails to stop to let them cross.” This is not true. Alternative 3b would allow people to cross the protected bike lane, then wait in a buffered area before crossing the two vehicle lanes separately, thanks to median refuge islands. At some intersections with concrete curb extensions (or "bulb-outs"), people would need to cross the bike lane and vehicle lane at the same time. Fortunately, this is a common design across Portland, and is supported by NACTO guidelines (pictured below). Bike boxes could add additional safety for both pedestrians and cyclists, but aren't necessary. “Alternative 2 is also likely to benefit pedestrians crossing side streets as they move along Hawthorne because of the center turn lane. Alternative 2 and Alternative 3 will both likely result in fewer gaps between cars for drivers turning left, but Alternative 2 gives drivers a place to wait for a gap and assess other drivers, bicyclists, and pedestrians moving through the intersection rather than feeling the pressure of blocking the through travel lane.” PBOT’s assumption that without a center turn lane, pedestrians would be in danger from drivers “feeling the pressure of blocking the through lane” seems to indicate that they view Hawthorne as a speed-oriented highway that drivers will continue to impatiently race through, rather than the relaxed neighborhood street it needs to become. If this assumption were true, we would likely see a high amount of crashes on two-lane commercial streets like NE Mississippi and NW 21st. But we don’t. These streets don’t have center turn lanes, yet they’re statistically much safer than Hawthorne—even east of Chavez, which is a High Crash Street and is the exact design PBOT plans to replicate for the rest of the corridor. Alternative 3b is best for pedestrian safety because it narrows Hawthorne to two 10-foot travel lanes, just like inner SE Division, NW 23rd, and NE Alberta, which are some of the safest, most pleasant streets for pedestrians in the city. 3. TransitPBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 is the best option for transit.” Why it’s false: Alternative 3b is the best option for transit because it poses no measurable transit delay, helps create a mode shift away from driving that will speed up buses, increases the street’s throughput with protected bike lanes, and sets Hawthorne up to be a car-free busway in the future. Fast transit is absolutely essential for Hawthorne. In PBOT's words: “According to the Transportation System Plan, Hawthorne is a Major Transit Priority Street, placing transit at the highest priority level in terms of prioritizing modes of travel on this street. Hawthorne is also part of the Rose Lane Project priority network, meaning that Hawthorne is an important corridor where the bus is experiencing lower speeds and reliability due to private vehicle congestion. Alternative 2 can best support speed and reliability for TriMet’s frequent Line 14 bus that directly connects downtown Portland to the Lents neighborhood.” If Alternative 2 can “best support speed” for Line 14, one might assume that Alternative 3b would create a significant transit delay compared to Alternative 2. After all, that was PBOT’s entire basis for claiming bike lanes are “bad for Climate and Equity” in their public survey. But it isn’t clear that Alternative 3b poses any measurable transit delay. According to PBOT, there are only three factors affecting transit times: 1) The mixing zone at Cesar Chavez. The Mid-project Report estimated Alternative 3b’s transit delay would be 8 to 16 minutes "primarily" due to the Cesar Chavez approach. However, the Decision Report states that adding a mixing zone to the Cesar Chavez approach “significantly reduces, but does not eliminate, the added transit delay we found in the earlier evaluation of Alternative 3.” How many minutes would this mixing zone eliminate from the transit delay? PBOT doesn’t say. But they do say that a mixing zone would all-but-eliminate transit delay for both Alternative 2 and Alternative 3b, so this shouldn’t be a deciding factor between the two alternatives. 2. Buses pulling in and out of bus stops. The decision report states “Alternative 3 would require buses to pull partially out of the travel lane and into the bike lane at bus stops,” and “in some locations, buses would then have to re-enter the stream of traffic when pulling away from stops. This adds new delay and conflicts.” It’s not clear how much “new delay” this conflict would add, but even if it were possible to quantify, it would likely be measured in seconds rather than minutes. More importantly, the delay and conflict can be completely resolved with prefabricated bus boarding islands like those recently installed on NW 18th, NW 19th, and NW Broadway. While these may be outside the scope of the Hawthorne Pave and Paint, they can easily and relatively affordably be added when funding is available, and will eliminate any additional stop-related bus delay as soon as they go in. 3. Left-turning vehicles. The only remaining cause of potential transit delay is buses “delayed by turning vehicles at side streets and driveways along the corridor, with the most significant delay caused by left turning vehicles blocking the through lane in Alternative 3. We expect some additional delay caused by right-turning vehicles yielding to bicyclists.” In a Q&A with the Bicycle Advisory Committee, PBOT says that “the issue of left turns is relatively minor and doesn’t factor into the traffic analysis in a significant way, and that left turning vehicles are “not the cause of the very high increase in travel time predicted by the traffic analysis. There just aren’t enough people turning left onto local streets to make that much of a difference.” To summarize:

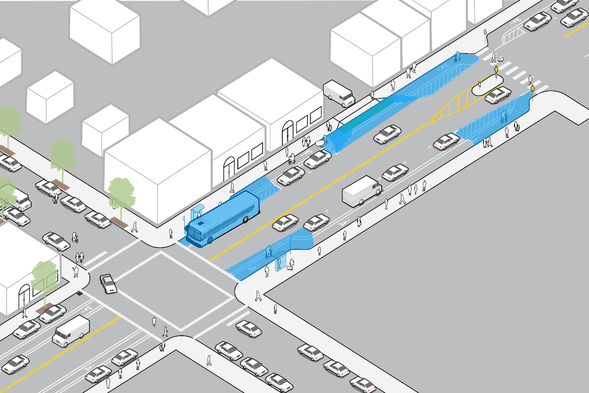

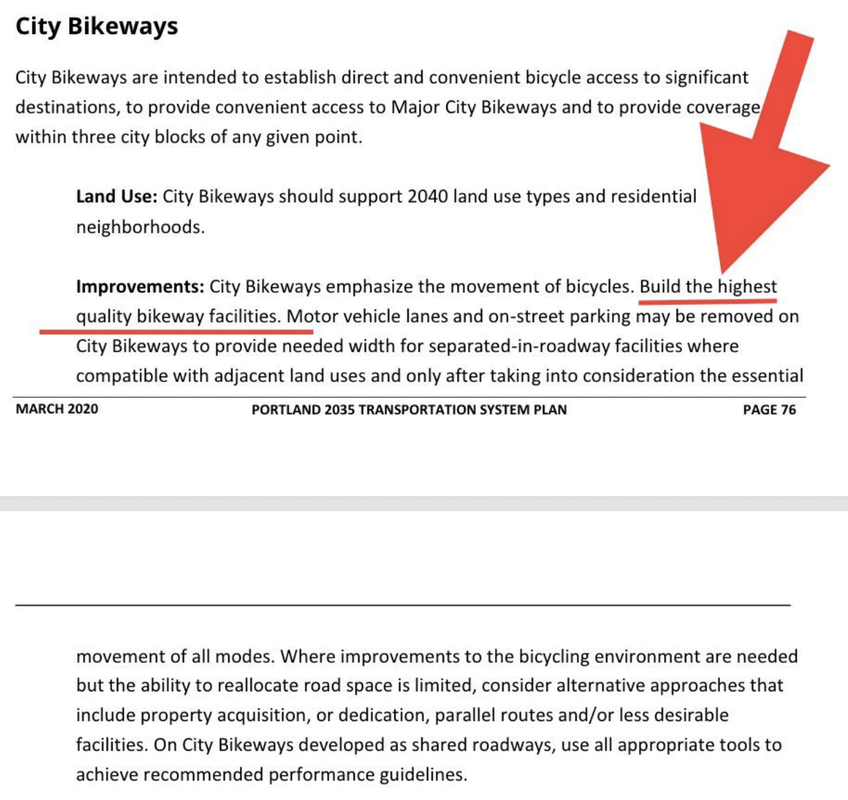

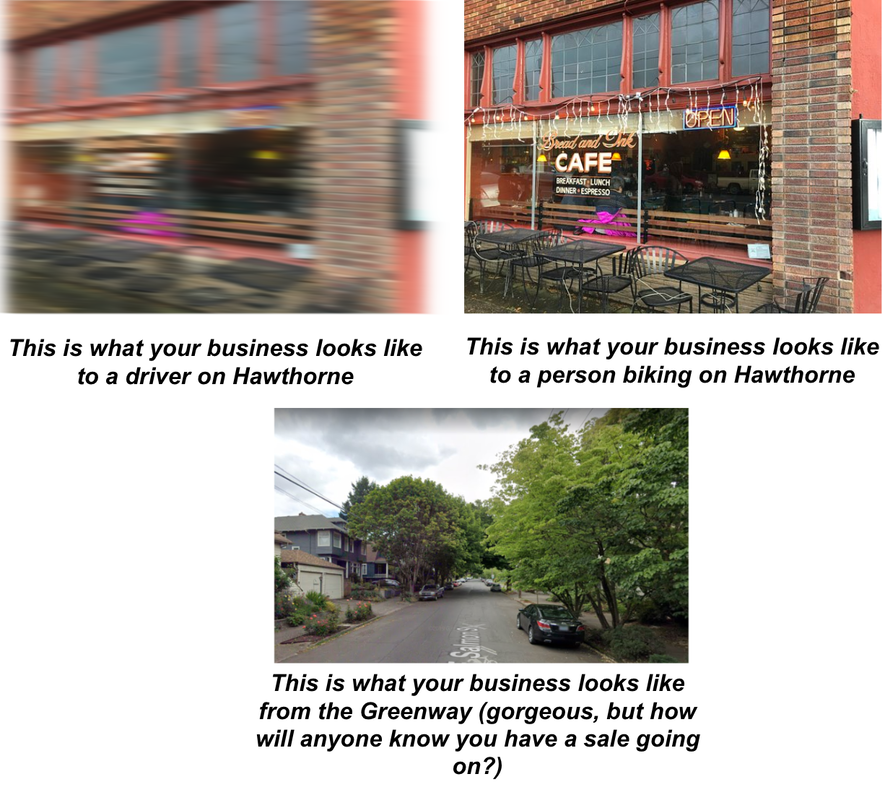

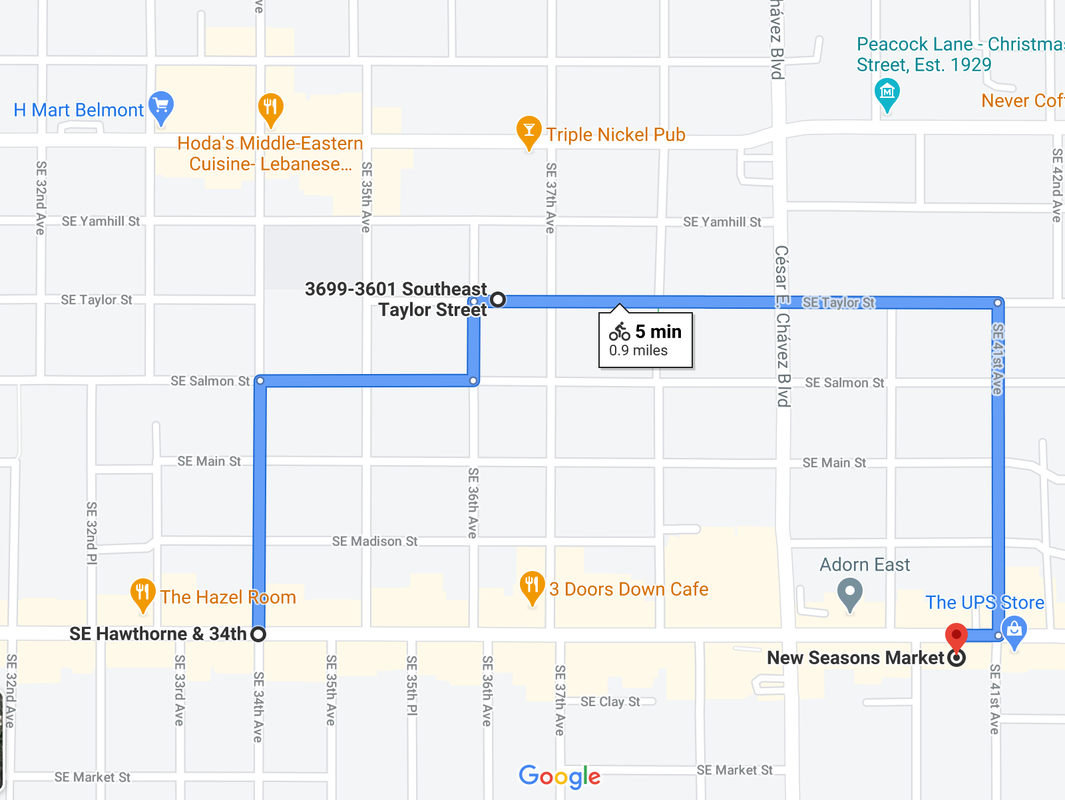

Given this information, it seems certain that Alternative 3b would not pose any significant (or even measurable) transit delay compared to Alternative 2. Since transit delay is one of the fundamental deciding factors here, it’s essential to know exactly how much delay is being projected in order to make an informed decision. But that question is not answered in any of PBOT’s documentation, and they denied our FOIA request to determine this information. What are they hiding? PBOT concludes this section with the following: “The lane configuration of Alternative 2 provides the flexibility for PBOT to consider additional bus priority lanes at other locations in the corridor where the bus is delayed. Alternative 3 does not offer this same flexibility to add additional transit priority improvements over time.” PBOT is saying that the center-turn-lane’s “flexibility” for “bus priority lanes” is so important that it should come at the expense of protected bike lanes and pedestrian median islands—despite zero indication that any intersections besides Cesar Chavez would cause enough of a delay to actually need this treatment. Since Hawthorne is a Major Transit Priority Street, we need to set it up for real transit success, which means making it a car-free busway (or a car-light busway by prohibiting thru-traffic and requiring people to turn at major intersections) as soon as possible. Alternative 2’s center turn lane—immortalized with 10-foot concrete median islands—renders this vision impractical. Alternative 3b makes it possible. 4. Emergency ResponsePBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 is the best option for emergency response.” Why it’s false: Alternative 3b is the best option for emergency response by creating mode shift (fewer cars means faster emergency response times) and by setting Hawthorne up to be a car-free busway in the future. Here’s what PBOT says: “According to City Policy, Hawthorne is a Major Emergency Response Street, placing emergency response at the highest priority level in terms of prioritizing modes of travel on this street. PBOT consulted with the Portland Fire Bureau and they indicated that Alternative 2 would be the safest way to improve and reduce the traffic and pedestrian crashes in this area of town and still provide the best emergency coverage.” The Fire Bureau has expressed similar concerns about various other lane reallocations in the past. This is not to diminish the need for fast emergency responses, only to note that we do not and should not design our city purely around the speed of our emergency vehicles. If emergency speeds are a top priority, Alternative 3b sets Hawthorne up to be a car-free busway in the near future, which is the best way to improve emergency response times in a dramatic, meaningful way. In the case of Alternative 3b, the large no-parking areas offer many places for people to pull cars aside for a passing emergency vehicle. Prohibiting cut-through traffic by requiring people to turn at major intersections (20th, 30th, 39th) is a potential stopgap solution that would reduce car traffic and improve emergency response times in the interim. 5. Low-Stress Bicycle AccessPBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 overall provides better low-stress bicycle access.” Why it’s false: Alternative 3b overall provides better low-stress bicycle access (and actually provides direct bicycle access in the first place, which Alternative 2 does not). Here's what PBOT says: “According to the Transportation System Plan, Hawthorne is a City Bikeway, placing bicycling at a medium level in terms of prioritizing modes of travel on this street. While the policy encourages providing bike lanes on City Bikeways, it also allows use of parallel bikeways with connecting routes as an alternative, if limited space makes it difficult to fully prioritize all modes.” Because Hawthorne is classified as a City Bikeway, the TSP says it should get the “highest quality bikeway facilities," and that PBOT should only “consider parallel routes” if two conditions are met: “After taking into consideration the essential movement of all modes,” and “when the ability to reallocate road space is limited.” But neither of these conditions are met. Alternative 3b poses no measurable transit delay in comparison to Alternative 2 (see Transit section above), so the essential movement of all modes is maintained. And Hawthorne is exceptionally wide for a neighborhood street (at 53 feet between curbs, compared to Division’s 36 feet), so the ability to reallocate road space is not limited. The TSP also says that “motor vehicle lanes may be removed on City Bikeways to provide needed width for separated-in-roadway facilities.” Removing the center turn lane from Alternative 2 provides the width required for protected bike lanes. Additionally, Portland’s Bicycle Plan for 2030 (as adopted by City Council in 2010) specifically dictates a “future separated in-roadway bikeway” for Hawthorne. “With the refinements, Alternative 2 prioritizes low-stress bicycle access to destinations on Hawthorne via north-south local streets connecting from the Salmon-Taylor and Lincoln-Harrison neighborhood greenways, which have been designed as calm, low-stress bike routes that appeal to a wide variety of people biking. By providing closely-spaced north-south neighborhood greenway connections, with good wayfinding and bike parking where these routes cross Hawthorne, we can improve bike access to businesses on Hawthorne. Once this expanded network is fully established, all destinations along Hawthorne will be within roughly a three-block walk from a designated bikeway. This map shows potential future bikeway connections to improve bike access." Greenway improvements are urgently needed, but they’re not a substitute for direct bike and scooter access on Hawthorne. Destinations are invisible from greenways, which hurts local businesses by discouraging people from shopping while biking. As every shop and restaurant owner knows, visibility and convenient access is everything. Additionally, traveling from one store to another along Hawthorne currently requires over a quarter-mile of out-of-direction travel to use low stress bicycle routes. In his blog Beyond The Automobile, Matt Pinder writes about the need for protected bike lanes on main streets, and how Greenways just don't cut it: "Our final thought about Portland’s Neighborhood Greenways is a cautionary one. With such a well-developed system of greenways spanning the City, many people on bikes choose to avoid major streets since there is frequently a Greenway within a few blocks. The success of Neighborhood Greenways in Portland has created a situation where there is less support for physically separated bike lanes along those main streets – many of which are lined with the businesses, restaurants and local shops that people on bikes want to get to. The Dutch experience is that while Greenways form an important role in the creation of a safe cycling network, they cannot exclusively form the entirety, or even the majority, of an effective cycling network. They must be used in combination with protected cycling lanes, multi-use paths and cycle tracks to build a complete network of AAA cycling infrastructure. Only when all of those tools are deployed with consideration towards constructing a complete network will cycling be seen as a safe, accessible and practical choice for a majority of residents in North America." [Emphasis added] This summer, as part of Central City in Motion, protected bike lanes are being added to Hawthorne from the Hawthorne Bridge to SE 12th. The Pave and Paint Project is an opportunity to connect that project to further east on Hawthorne, eventually creating the complete network of protected cycling lanes that Pinder argues is essential to building a city “where cycling will be seen as a safe, accessible, and practical choice for a majority of residents.” A network is only as good as its missing links. PBOT proceeds to give four reasons why they don’t think Alternative 3b would provide adequate safety for people biking on Hawthorne: 1) There would be a mixing zone at Cesar Chavez: “On the approaches to SE César E Chávez Boulevard, bicyclists would enter “mixing zone” shared with buses and right turning vehicles, and buses would block bicycle travel at the far-side stops in both directions.” While a bus-bike mixing zone is not ideal from a safety standpoint, a de facto mixing zone exists here today, which would continue to exist in Alternative 2 for those who choose to bike on Hawthorne. In comparison, Alternative 3b’s painted mixing zone would be a huge improvement by at least formalizing the design and reducing confusion for bikes and buses. PBOT continues to build mixing zones for other new bike lanes (such as the recently upgraded SE Foster and 82nd), so they clearly view them as an acceptable design. 2) A few very short stretches wouldn't have a buffer: “At median refuge islands along the corridor, the bike lanes would narrow to five feet wide, with no painted buffer.” PBOT builds many bike lanes with portions that are unbuffered. A few very short stretches (as in just a dozen feet long or so) with no painted buffer is a fine compromise for safe, protected bike lanes on the rest of the corridor. Worst of all, Alternative 2’s concrete refuge islands would further prevent the possibility of building protected bike lanes in the future by creating even more situations where this buffer-less design would be necessary. 3) Bikes and buses would need to mix at bus stops: “At bus stops, the bus would pull into the bike lane to stop.” Again, pre-fab bus boarding islands will solve this issue. Although they’re outside the scope of this project, they can be seamlessly added as soon as funding becomes available. Until that happens, bikes and buses can share the lane. While it’s not an ideal design, it’s an acceptable stopgap solution, and is a design that exists in many bike lanes around the city. 4) The crossing islands would be too narrow for unusually long bikes to fit fully inside of: “Both Alternative 2 and 3 make improvements for bicyclists crossing Hawthorne by including new median refuge islands at key locations to facilitate crossings for both pedestrians and people biking. In Alternative 2, the refuge islands can be 8 to 10 feet wide. In Alternative 3, refuge islands would only be 6 feet wide. Some types of bicycles, such as the one shown here, are longer than 6 feet and may not be fully protected by a 6-foot refuge island.” A "bicyclist crossing Hawthorne" using a median refuge island would typically be considered pedestrian, since they’d presumably be walking their bike (a person riding their bike would typically be crossing Hawthorne in the roadway—rather than in the crosswalk—where the width of median refuge islands aren’t an issue). While some types of bicycles are longer than six feet, the following sequence of events would need to occur in order for their long bike to pose a safety issue while waiting in the median:

Assuming the refuge island is a sufficient length (6.5 feet?), it might also be possible to simply turn the long bike diagonally, offering it full protection in this rare circumstance. 6. Flexible Curb Zone SpacePBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 offers the most flexible curb zone space.” Why it’s false: Alternative 3b offers the most flexible “floating” curb zone space, and brings the most amount of people to local businesses using that space. “According to the Transportation System Plan, Hawthorne is a “Civic Main Street,” which emphasizes the importance of a flexible curb zone space to support local businesses. The curb zone can be used for a variety of supportive activities like street seats, parklets, bike corrals, bikeshare stations, bus stops, loading zones, pick-up/drop-off zones, and on-street parking.” “Alternative 2 does not require changes to the curb zone beyond limited parking removal at street corners to improve safety.” Despite overwhelming evidence that removing parking at street corners dramatically improves safety, Alternative 2 does not do nearly enough to accomplish this; in fact, it hardly does anything. In a six-block stretch of Hawthorne, PBOT’s plans show just one parking spot removed for better sightlines: “By reducing the travel lanes from four to three, Alternative 2 provides more space and buffer for uses in the curb zone beyond parking, including “Healthy Business” uses, loading/unloading, bike corrals, or expansion of pedestrian space.” The implication here is that removing some curb zone space isn’t an acceptable tradeoff for multimodal safety. But removing parking near intersections would dramatically increase visibility and reduce turning crashes for all modes, making it much safer for people walking and biking to cross the street. PBOT does not currently have any official policies or standards for this intersection-adjacent curb zone buffer space, but bike parking, e-scooter parking, low-profile greenery, and even public seating would all likely offer enough sight distance to be acceptable uses for this space. Businesses with curb zone space near intersections could also utilize curb space on the side streets they're adjacent to. Whenever possible, these side streets could be prioritized for car-free plazas, giving businesses much more space and comfort than a single parking space next to noisy traffic. “Parking and any other curb zone uses would not be curb-side anymore, instead “floating” between the bike lane and travel lane with minimal buffer. Given the constrained dimensions of Hawthorne, and the need to cross the bike lane to access it, the floating space that remains is much less likely to be used as additional pedestrian space or for Healthy Business uses. “ If floating street seating isn’t a design PBOT is willing to explore, it would mean that any street that currently has street seating is ineligible for protected bike lanes. This is an unsustainable policy, as many streets that are designated as City Bikeways (E Burnside St, SE Morrison St, SE Belmont St) and Major City Bikeways (NE Broadway, NE 28th Ave, N Williams Ave) currently have lots of curbside street seating. Floating curb zone space has proven to work well in other cities. Here's an example from NYC: If floating curb space can work in a city as busy as NYC, it can work in Portland. Conflict can be mitigated with signage, crosswalks on the bike lane, and other simple design treatments to encourage awareness among all users. Would there still be some risk of bike-pedestrian conflict? Of course; accidents happen. But fatal bike-pedestrian crashes are exceedingly rare, while fatal bike-car crashes are horrifyingly commonplace—especially on wide, arterial streets like Hawthorne that lack protected bike lanes. The benefit of protected bike lanes with a floating curb zone vs. no bike lanes and a regular curb zone is clear: The former is objectively, significantly safer overall. This is supported by data. In North Carolina, from 1997-2014, out of over 44,000 recorded crashes, there is no record of a bicyclist hitting a pedestrian. Similar data from NYC—a much busier city, with many more cyclists than Portland—shows that out of 45,775 vehicle collisions in 2018, 98% were caused by cars, and only 2% of them were pedestrians hit by cyclists. And of that 2%, only one pedestrian fatality occurred—a .00002% fatality rate (and that sole fatality was caused by a cyclist running a red light). Cars are statistically much, much, much, much, much, much more dangerous than bikes, so we should design Hawthorne to mitigate that danger as much as possible, rather than worrying about edge cases that are unlikely to ever occur. EDIT: A reader has pointed out that PBOT actually does have experience with floating street seating. On SW 2nd Ave, Dan and Louis Oyster Bar has street seating in the parking lane across from the protected bike lane, pictured here: 7. Citywide Goals on Equity and ClimatePBOT’s claim: “Alternative 2 advances citywide goals on equity and climate.” Why it’s false: Alternative 2 does not advance citywide goals on equity and climate because it fails to adhere to Portland’s 2015 Climate Action Plan (which calls for a 40% reduction in driving and a 20% increase in biking) and the Climate Action Through Equity Plan (which calls for “more bike-friendly communities that encourage active transportation"). Alternative 3b advances citywide goals on equity and climate by building the infrastructure necessary to create this mode shift and achieve these goals. PBOT claims that Alternative 2 will "advance equity" and "address structural racism:" “With guidance from PBOT’s Strategic Plan, when we make decisions, we ask: Will it advance equity and address structural racism? Will it reduce carbon emissions? If the answer is “no” to either of these questions, we need to re-evaluate. In this case, with Alternative 2 as the selected design, the answer to both questions is yes.” Alternative 2 proposes no change whatsoever to Hawthorne East of Cesar Chavez, and maintains the car-centric status quo west of Cesar Chavez. How exactly will this reduce carbon emissions? PBOT makes no further mention of carbon emissions anywhere else in the Decision Report, so their basis for this claim is unclear. The only way to meaningfully reduce carbon emissions is to reduce the amount of people driving, and the only way to reduce the amount of people driving is to offer people safe, attractive alternatives. By freeing people from the financial burden of car ownership and offering a safe, attractive alternative to driving, Alternative 3b will help reduce carbon emissions and address structural racism. Alternative 2 will not. A faster bus would help get people out of their cars, too, but in order for a mode shift to occur, riding the bus must be faster than driving, which won’t happen if buses share a lane with cars. Making Hawthorne a car-free busway is the best way to accomplish this, and Alternative 3b sets the stage for this, while Alternative 2’s center turn lane and concrete median islands actively prevent it from happening. Let's talk about equity. According to extensive research compiled by PeopleForBikes’ Green Lane Project:

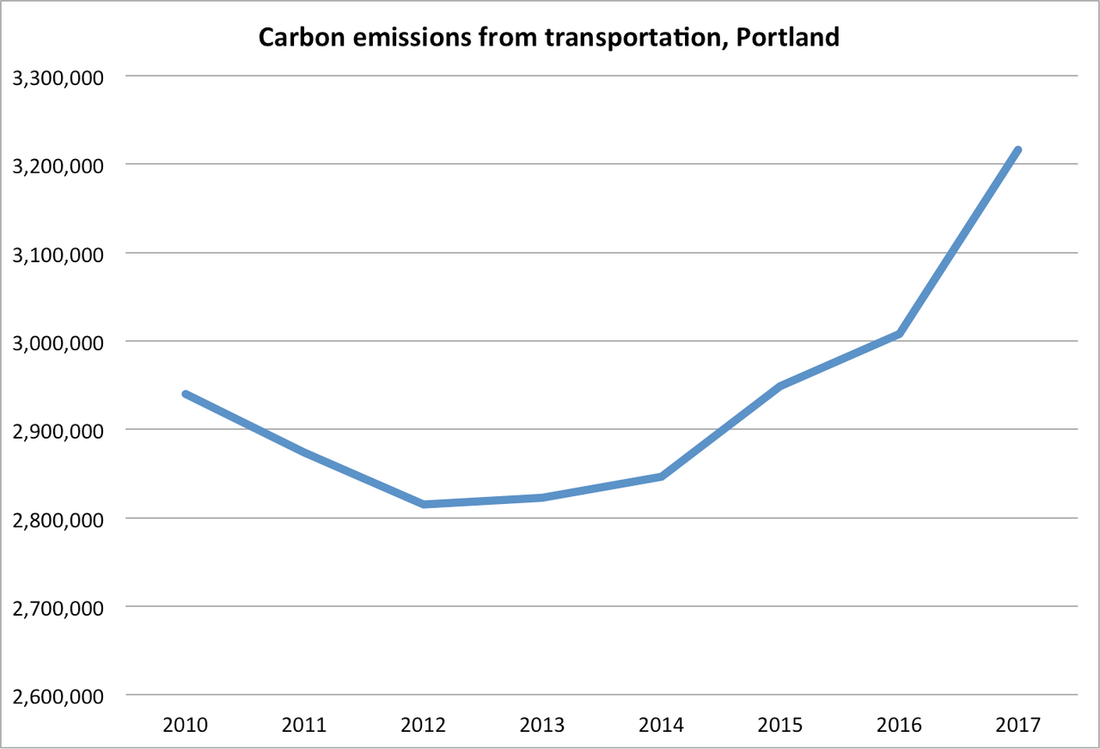

So how could Alternative 2, which does not include protected bike lanes, possibly be more equitable? Again, the only justification PBOT offers is that transit times would be impacted—which, as we’ve just explored in Section 3, does not seem to be true. If public agencies like PBOT are going to start applying equity and climate lenses to projects (which they should), we need to hold them accountable for doing it the right way—using facts and data—rather than using them as propagandistic weapons to justify some pre-determined outcome that prioritizes speed, throughput, and parking for single-occupancy vehicles. “Alternative 2 improves safety and access for climate-friendly active transportation and transit modes. It focuses on pedestrian safety, with investments that will benefit people of all ages, people with disabilities, and people crossing the street on bikes. It avoids overly negative impacts for equity priority areas further east of Hawthorne, enhances transit reliability along the corridor, and it preserves the opportunity to further enhance transit priority to and from these areas if needed. “ It can’t be stressed enough: The only advantage Alternative 2 has for pedestrian safety is that its 10-foot median refuge islands would be slightly wider than Alternative 3b’s 6-foot refuge islands. But this would come at the expense of safety for those on bikes and scooters, drivers who would benefit from better sightlines at intersections, and pedestrians who would benefit from narrower crossing distances and calmer traffic. “Alternative 2 uses our limited resources wisely, leveraging the investment in repaving while preserving more discretionary funding for other areas of the city with greater infrastructure needs.” This is why it’s crucial that Hawthorne gets the safety upgrade it desperately needs now, while we have the opportunity and funding available. Otherwise, it may never happen. Conclusion: Why It’s So Important To Get This RightPublic agencies are hard to keep accountable. Police departments brutalize their communities, water bureaus fail to keep their city’s water free from toxic waste, and transportation departments build and maintain streets that are designed to kill people. While PBOT has generally upheld a good reputation, the Pave and Paint Project has shed light on their recurring fear of making bold, progressive decisions. We’ve seen this play out with other recent projects (such as not building protected bike lanes on N Denver Ave, citing “concerns” about garbage removal), but the Pave and Paint Project has revealed—with more certainty than ever—their willingness to lie in order to justify those decisions, and their systemic disinterest in taking meaningful action to free our city from the shackles of car dependency. This isn’t just about adhering to policies or drawing lines on a map. It’s about creating a street that prevents people from dying. And as it stands, Hawthorne is a deadly street to walk, bike, and drive on, and lives and limbs will continue to be lost unless we solve this problem. Alternative 3b offers a chance to make meaningful progress towards achieving this goal. "One thing that I don't think a lot of Americans are aware of is how far behind we are in bicycle and pedestrian safety. In other words, other developed countries are safer to walk or bike in than American streets typically are. The design choices we make about how fast cars move, or whether there are bike lanes and sidewalks sharing the space with travel lanes—all of this is part of that picture, and is an example of what it means to have a truly forward-looking approach on infrastructure.” —Pete Buttigieg, Secretary of Transportation (Source: Twitter) The best time to build a bike lane was 20 years ago. The second best time is now. With priorities shifting to more urgent streets in East Portland, Hawthorne will likely not have another chance to be made safer for at least another decade. We cannot continue to defer bold, yet necessary decisions to free our city from car dependency and traffic violence. Future generations of Portlanders are counting on us to start doing that work today, and Alternative 3b offers a shovel-ready opportunity to transform Portland into the more walkable, bikeable, transit-friendly city it has so much potential to become. Many thanks to Kiel, Tim, Buff, Michael, Doug, Chris, Scott, David, Clint, and Eric for helping put this piece together. |

AuthorZach Katz is a former member of Portland's Pedestrian Advisory Committee and enthusiastic about safe streets. He's lived car-free in Boston, New York City, and Los Angeles, and now calls Portland home. Archives

May 2021

Categories |

|

|

Questions? Suggestions? Press inquiries? Get in touch.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed